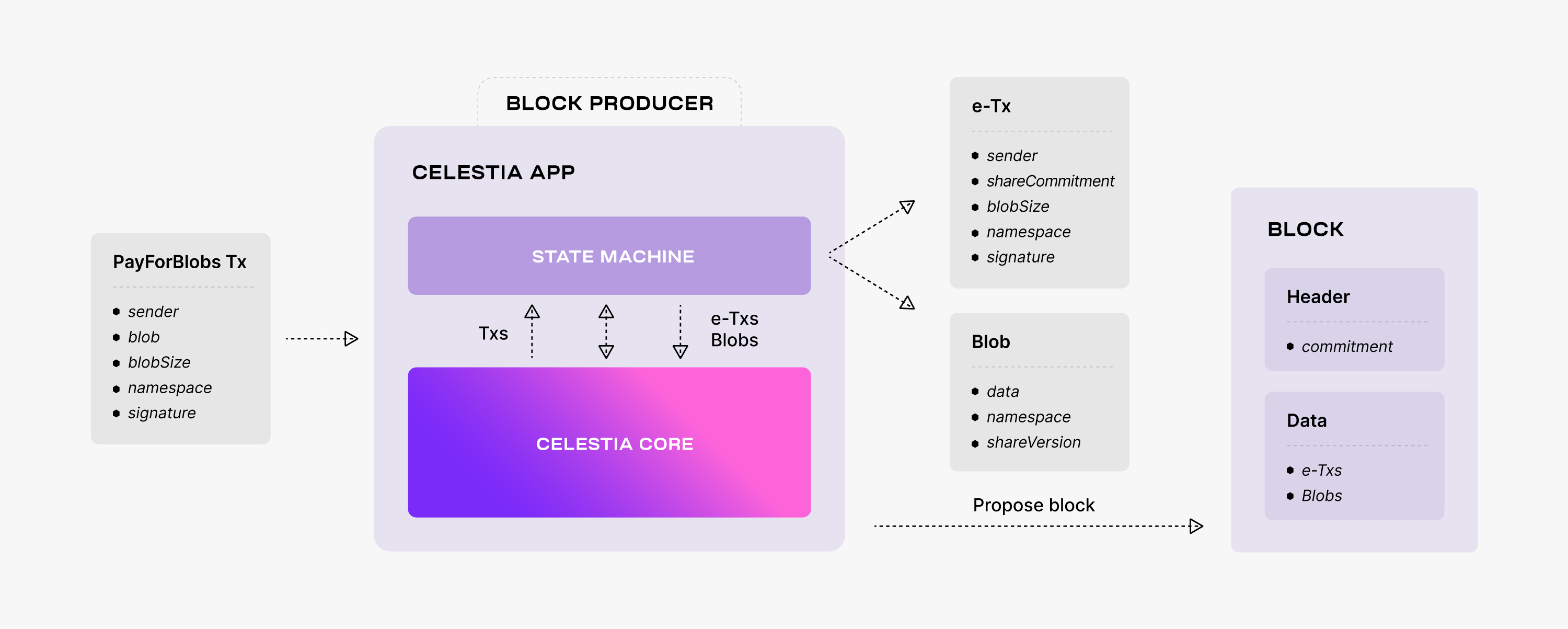

The lifecycle of a celestia-app transaction

Users request the celestia-app to make data available by sending PayForBlobs transactions. Every such transaction consists of the identity of the sender, the data to be made available, also referred to as the message, the data size, the namespace, and a signature. Every block producer batches multiple PayForBlobs transactions into a block.

Before proposing the block though, the producer passes it to the state machine via ABCI++, where each PayForBlobs transaction is split into a namespaced message (denoted by Msg in the figure below), i.e., the data together with the namespace ID, and an executable transaction (denoted by e-Tx in the figure below) that does not contain the data, but only a commitment that can be used at a later time to prove that the data was indeed made available.

Thus, the block data consists of data partitioned into namespaces and executable transactions. Note that only these transactions are executed by the Celestia state machine once the block is committed.

Next, the block producer adds to the block header a commitment of the block data. As described in the "Celestia's data availability layer" page, the commitment is the Merkle root of the

- It splits the executable transactions and the namespaced data into shares. Every share consists of some bytes prefixed by a namespace. To this end, the executable transactions are associated with a reserved namespace.

- It arranges these shares into a square matrix (row-wise). Note that the shares are padded to the next power of two. The outcome square of size

is referred to as the original data. - It extends the original data to a

square matrix using the 2-dimensional Reed-Solomon encoding scheme described above. The extended shares (i.e., containing erasure data) are associated with another reserved namespace. - It computes a commitment for every row and column of the extended matrix using the NMTs described above.

Thus, the commitment of the block data is the root of a Merkle tree with the leaves the roots of a forest of Namespaced Merkle subtrees, one for every row and column of the extended matrix.

Checking data availability

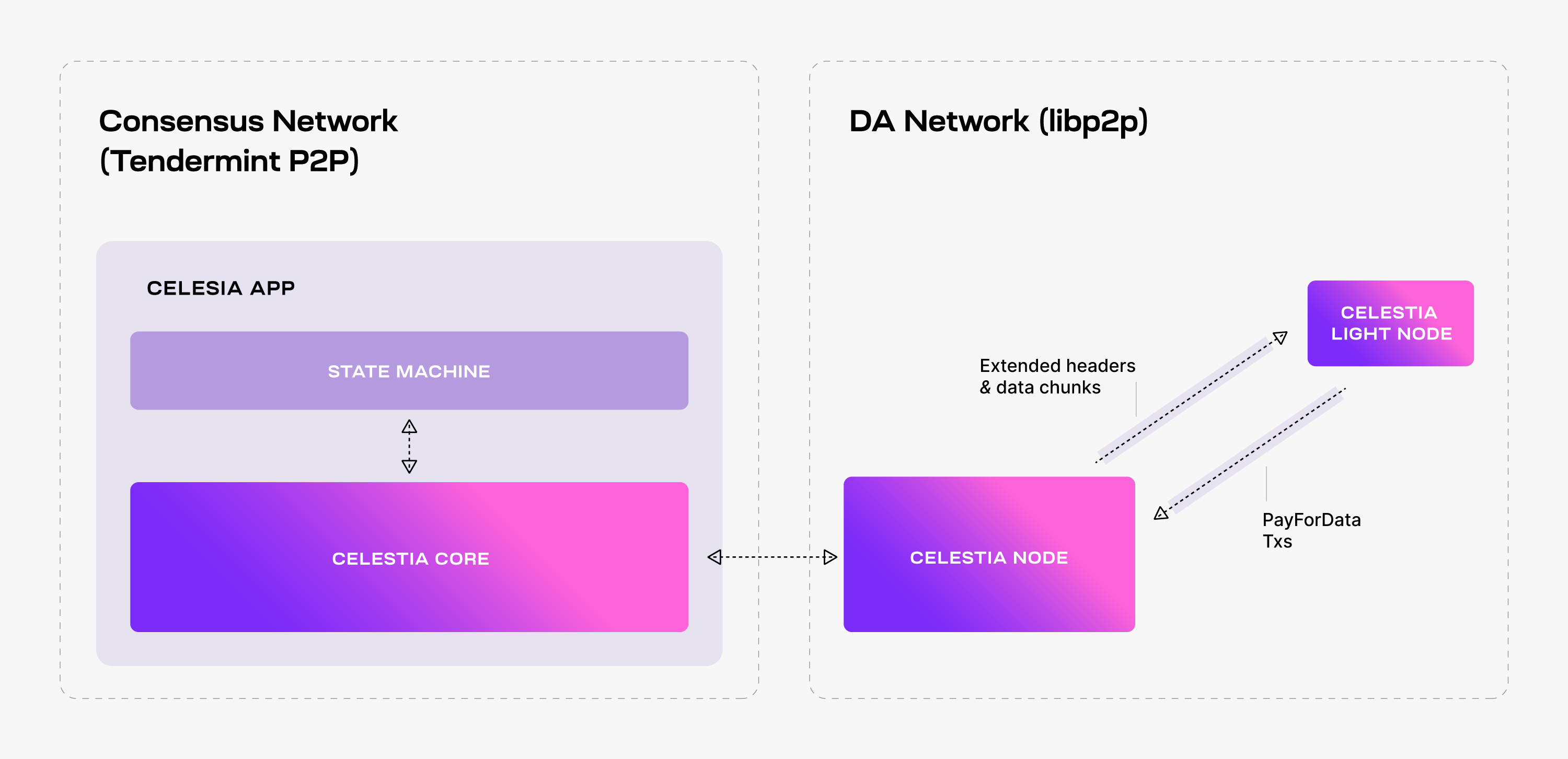

To enhance connectivity, the celestia-node augments the celestia-app with a separate libp2p network, i.e., the so-called DA network, that serves DAS requests.

Light nodes connect to a celestia-node in the DA network, listen to extended block headers (i.e., the block headers together with the relevant DA metadata, such as the

Note that although it is recommended, performing DAS is optional -- light nodes could just trust that the data corresponding to the commitments in the block headers was indeed made available by the Celestia DA layer. In addition, light nodes can also submit transactions to the celestia-app, i.e., PayForBlobs transactions.

While performing DAS for a block header, every light node queries Celestia Nodes for a number of random data chunks from the extended matrix and the corresponding Merkle proofs. If all the queries are successful, then the light node accepts the block header as valid (from a DA perspective).

If at least one of the queries fails (i.e., either the data chunk is not received or the Merkle proof is invalid), then the light node rejects the block header and tries again later. The retrial is necessary to deal with false negatives, i.e., block headers being rejected although the block data is available. This may happen due to network congestion for example.

Alternatively, light nodes may accept a block header although the data is not available, i.e., a false positive. This is possible since the soundness property (i.e., if an honest light node accepts a block as available, then at least one honest full node will eventually have the entire block data) is probabilistically guaranteed (for more details, take a look at the original paper).

By fine tuning Celestia's parameters (e.g., the number of data chunks sampled by each light node) the likelihood of false positives can be sufficiently reduced such that block producers have no incentive to withhold the block data.